By continuing to browser our site and use the services you agree to our use of cookies, Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.

Li Yuemei (1918–1968), female, was born into an overseas Chinese family in Penang (now Malaysia), with ancestral roots in Taishan, Guangdong. In late 1938, when China’s lifelines were cut off by invading Japanese forces, she disguised herself as a man and joined the Penang Volunteer Mechanical Engineering Team. She returned to China to take part in transport operations along the perilous Burma Road, later hailed as the “lifeline of resistance.”

Wanding in Ruili, Yunnan, a small town on the China–Myanmar border, marked the Chinese terminus of the Burma Road. Not long ago, reporters from Global People visited the Memorial Hall for Nanyang Overseas Chinese Volunteer Drivers and Mechanics.

Few visitors notice that there are exactly 50 steps from the entrance to the exit of the memorial hall, a quiet and austere tribute to the more than half a million tons of military supplies that the Nanyang Overseas Chinese Drivers and Mechanics (Nanqiao Jigong) rushed along the Burma Road around the clock. Inside the hall, yellowed photographs, faded overalls, rust-stained tools, and bundles of letters home are neatly arrayed. A wall map traces the wartime routes used then, as if carrying us back across time and space.

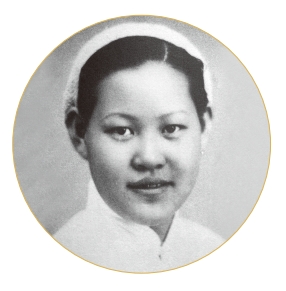

On the “Wall of Heroes,” portraits and names of 700 Nanqiao Jigong look out at visitors. Amid the many male faces, one woman with a neat bob and a radiant smile stands out. She was Li Yuemei, a “modern Mulan” who helped open the wartime lifeline along the Burma Road during the War of the Chinese People’s Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

A child stands before the “Wall of Heroes” at the Memorial Hall for Nanyang Overseas Chinese Volunteer Drivers and Mechanics on July 27, 2025.

A group photo taken in February 1939 shows the 32 members of the Volunteer Mechanical Engineering Team of Penang Machinery Company on the eve of their departure; Li Yuemei is the sixth from the left in the second row.

“I returned to my motherland knowing there was hardship waiting for me.”

In the winter of 1938, Penang’s weather was as balmy as ever. However, anxiety was rippling through the local overseas Chinese community. Dire reports from the front flooded in: Central, Eastern, and Southern China were falling in succession, with 95% of the nation’s industry and half of its population already under Japanese occupation.

Li Yuemei, who had just turned 20, followed the news as closely as her parents did. Since the Lugou (Marco Polo) Bridge Incident of 1937, this tall, spirited, and resolute girl and her close friends had often taken to the streets to sell flowers to raise funds in support of the motherland’s War of Resistance.

One day, a recruitment notice from the Penang Machinery Company stopped her in her tracks: “Recruiting volunteers aged between 20–40, of good character, capable of driving and proficient in vehicle repair…” With Japan having cut off China’s southeastern sea and land routes, there was a pressing need to restore the Burma Road, which had become the southwest’s vital wartime lifeline. Thousands of trucks and mountains of supplies needed to be moved, yet the Nationalist government was short of drivers and mechanics. In response, the prominent Overseas Chinese business leader and philanthropist Tan Kah Kee issued a call to “Recruit Drivers and Mechanics to Return and Serve the Motherland.”

After reading the notice, Li felt she met all the physical requirements, though she could neither drive nor repair vehicles. “Mastering mechanics in a short time might be tough,” she thought to herself, “but driving shouldn’t be so hard!” She and a friend then borrowed a 21-seat bus. After a little over four hours of practice, she was already driving competently and confidently. Not long afterward, she obtained her driver’s license.

“I want to sign up!” At the Penang Machinery Company’s recruitment desk, Li’s determination was met with an unequivocal response: “We don’t recruit women drivers or mechanics.”

“I can drive, I’m fit, and I’m fluent in Chinese!”

“Still no! Rules are rules.”

Unable to persuade the registrar, she had no choice but to turn away and step out of the line, thinking to herself: “I must find a way to go back and serve my motherland!” Back home, noticing that her younger brother Li Jinrong was about her build, she immediately hatched a plan. A few days later, she cut off her long hair, put on her brother’s clothes, and headed to another registration site far from home.

This time, presenting as a young man, Li Yuemei was finally accepted and became one of the 32 final recruits. Before her departure, a mandatory medical exam revealed her sex. Even so, perhaps impressed by her resolve and resourcefulness, the team leader allowed her to remain.

News that a “Mulan” had joined the volunteer team quickly caught the attention of Nanyang Siang Pau. With the team leader’s consent, Li gave an interview.

“Do your parents support your decision to return to China?”

“Of course they do. There are nine siblings in my family. Even if one or two were sacrificed for the motherland, so be it.”

The reporter noted that many overseas Chinese lived a comfortable life, whereas conditions on the Burma Road were extremely arduous. Li responded calmly: “I’m not afraid of hardship. My embattled motherland needs me, and I will endure any difficulty for her.”

Li Yuemei in standard-issue fatigues

“Hands on the wheel, patriotism in our hearts”

In the spring of 1939, after more than a month on the road, Li Yuemei and her team arrived in Kunming, Yunnan. There she met other contingents of patriotic youths from Southeast Asia: Singapore, Malaya (now Malaysia), Siam (now Thailand), and elsewhere. By August 1939, their ranks had swelled to over 3,200. They would later collectively be known as the “Nanqiao Jigong”.

For operational convenience, Li continued to pass as a man. She and her teammates first underwent training, honing their driving skills by day and cramming into small makeshift huts by night. The weather in Kunming is springlike year-round, but compared with Penang, it still felt decidedly cold. With wartime shortages, a single wool blanket was all they had to ward off the chill. Rations were also strictly allotted: eating commenced on the first whistle and finished a few minutes later on the second whistle, regardless of how full one was.

After training, Li was assigned to the Guizhou Red Cross Society and given a daunting task: hauling supplies along the Burma Road.

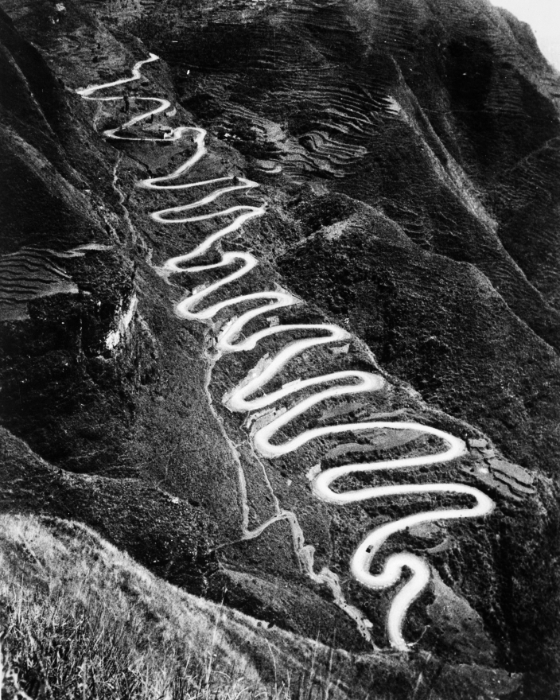

During the road’s construction, one out of every ten workers paid with their lives, felled by accidents or enemy attacks. From Kunming to Lashio in Myanmar, the 1,146-kilometer dirt road writhed like a yellow serpent. At times, even one truck could hardly pass, and at points, drivers faced five or six hairpin turns within a single minute. Convoys had to crest the precipitous Hengduan, Nu, and Gaoligong ranges, all rising above 3,000 meters, cross the torrenting Yangbi, Lancang (Mekong), and Nu (Salween) rivers, and push through ancient, fever-ridden wilderness long feared as the “land of miasma,” where settlements were few and far between.

The Burma Road in June 1944

Ye Yufang, a researcher at the Taishan Museum in Jiangmen, Guangdong, told the reporters that the Burma Road was not only treacherous in its own right but also subject to frequent Japanese bombing and strafing. Meanwhile, the Nanqiao Jigong were pressed for time, drove aging vehicles, and hauled over-capacity loads, all of which further heightened the risks of every run.

Every time she hit the road, Li’s patience and stamina were pushed to the limit. A slight slip of the wheel could send her and her truck plunging off a cliff or into a river, vanishing without a trace.

Sustaining China’s war effort like a steady transfusion, the Burma Road was a prime target for the Japanese army. Therefore, Li trained herself to be extra alert. At the first sign of enemy aircraft, she would cut the motor, pull to the side of the road, and conceal the truck. If time allowed, she would also camouflage it with leaves and mud.

With atrocious road conditions and periodic air raids, overnight stops on the roadside or long waits for emergency repairs became routine. Although there were way stations dotted along the route, just like most of her comrades-in-arms, Li usually slept in the truck itself to guard the cargo and spare parts.

True to her promise of serving her country and enduring hardship, Li never uttered a word of complaint. To those around her, the fine-featured “young man” was diligent and well-liked, and almost no one realized that she was a woman.

A display of one of the vehicles used on the Burma Road at the Memorial Hall for Nanyang Overseas Chinese Volunteer Drivers and Mechanics (Photo: Liu Shuyang / Global People)

“Who is Li Yuemei?”

By 1940, Li had served for a year on the Burma Road. Reports of fallen drivers and mechanics arrived with grim regularity. She mourned them and reminded herself to be doubly careful.

One day, when taking a sharp hairpin, her truck overturned. She was gravely injured and couldn’t move. Barely conscious, she had no idea how long she had lain there for. It was at this moment that a voice cut through the haze: “Are you all right? Hang in there!”

The rescuer was Yang Weiquan, a Nanqiao Jigong of Hainanese origin. He hauled Li from the mangled cab and raced her to the nearest hospital.

Her life was saved, but her identity as a woman was once again exposed. The press hailed her as a “modern Mulan,” and her story caused a huge sensation. The renowned activist Ho Hsiang-ning presented her with a calligraphic inscription reading “巾帼英雄” (“Heroine”) in her honor. After Li recovered, she was transferred to the infirmary as a nurse, continuing to serve the Burma Road and the country in another capacity.

According to Luo Yunhui, director of the Memorial Hall for Nanyang Overseas Chinese Volunteer Drivers and Mechanics, after 1938, the Burma Road became China’s only overland link to the outside world, carrying about 90 percent of international supplies including weapons, fuel, medicines, raw materials, and industrial equipment, with military materiel alone exceeding 500,000 metric tons.

“These supplies were vital to sustaining China’s war effort. For three and a half years, from December 1938, when transport on the Burma Road began, to May 1942, when Japan occupied Burma, and apart from the three months when the British army deliberately closed the road, the road only became impassable for a total of 13 days, 10 hours, and 15 minutes. In the race to move those shipments, roughly one-third of the Nanqiao Jigong laid down their lives on the road,” Luo added.

Spurred by his sister’s example, her younger brother Li Jinrong, who was two years her junior, also joined the eighth cohort of the Nanqiao Jigong in 1939. Fortunately, both siblings endured and lived to see victory.

Li Yuemei (far left) returned to Penang and reunited with her family after the victory against the Japanese.

In 1946, Li set out for home with Yang Weiquan, the man who had once pulled her from the wreckage. Their bond, forged in that life-and-death moment, deepened, and eventually they got married.

Soon after the family’s reunion, the couple moved and settled in Myanmar. In 1954, during Premier Zhou Enlai’s visit, Li attended a forum as a representative of the overseas Chinese community. Learning of her story, Zhou praised her as a “heroine” again and again.

In Myanmar, Li and Yang ran a café and lived quietly. Though life was comfortable, her heart remained with her homeland. In 1965, Yang stayed behind while Li returned to China with eight of their ten children. After a period of study, her son, Yang Shanguo, and daughter, Yang Lingmei, were both admitted to the Beijing Institute of Foreign Languages (now Beijing Foreign Studies University), to the family’s great delight.

Yang Shanguo was born in 1948 and has since passed away. However, his wife, Yin Fenge, shared these anecdotes: When we first met, he said with pride to me, ‘My mother is a hero of the War of the Chinese People’s Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.’” She added, “In his later years, after we got a smart speaker at home, whenever he missed his mom, he would ask the speaker over and over, ‘Who is Li Yuemei?’ The speaker would then reply, ‘Li Yuemei, born in 1918…’,” Yin told Global People.

What comforts Yin is that, although the grandchildren once doubted their grandmother’s story as “too ideal to be true,” in recent years, they too have begun to learn about that period of history in earnest.

“Travel is getting harder as I get older. The commemorations I once attended myself I now entrust to the younger generation. No matter what happens, the spirit of the Nanqiao Jigong must be passed down from one generation to the next!” she exclaimed.

For years, Yang Shanguo and his siblings had one abiding wish: to find their mother’s long-lost relatives in Southeast Asia. The responsibility has now passed to Yin. “After our mom returned to China, she lost contact with her family in Southeast Asia. She had eight siblings. Surely some kin must be still out there; we just haven’t found them yet.”

Yin has imagined the reunion many times—perhaps in Hainan, to visit Li and Yang’s graves together; perhaps in Malaysia, to seek out traces of their ancestral home… “We only want to ask some simple questions, on our mother’s behalf: Are our relatives well? How’s everything going with them after all these years?”

Over 80 years ago, it was this very feeling that sustained Li Yuemei and more than 3,200 Nanqiao Jigong as they threw themselves into the war. Believing that, no matter the distance between us, we are always one family, sharing honor and hardship alike, forever bound by blood.

Hainan FTP Extends Corporate Income Tax Incentives till 2027

04:40, 24-August-2025Li Yuemei: the “Mulan” of Nanqiao Jigong

04:37, 24-August-2025Discovering Mysteries Season 5, Episode 12: Love Ballad of the Rainforest Frog

05:26, 22-August-2025A Hainan media tour for journalists across 9 Asian countries

05:26, 22-August-2025Expert Talks: Hainan: New Foreign Investment Hotspot

05:26, 22-August-2025Chen Zhaozao: Life and Death on the Burma Road

05:26, 22-August-2025By continuing to browser our site and use the services you agree to our use of cookies, Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.