By continuing to browser our site and use the services you agree to our use of cookies, Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.

Chen Zhaozao (1900-1987) was a native of Lehui County (now Qionghai City), Hainan. At 16, he left Hainan for Singapore to support his impoverished family. In 1939, responding to the call from his homeland for assistance, he enlisted in the second cohort of Nanyang Overseas Chinese Volunteer Drivers and Mechanics (Nanqiao Jigong), returning to China to provide vital support to China in its war of resistance against Japanese aggression.

Just like all the other summers that preceded it, the summer of 2025 in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province, is pleasantly cool. In Chen Daya's unassuming apartment in an equally modest, aging apartment block shaded by trees, something that would otherwise go unnoticed save for her unwitting glances stands out: two photos hanging on the wall next to the door to her study.

Seated in a rattan chair, she subconsciously turned her eyes toward a photo of her father on the wall opposite as she talked about him in an interview with Global People. For much of her life, she knew very little about him—a lack of understanding peppered with misconceptions. It wasn't until 13 years after his death, in the autumn of 2000, when she retraced the Burma Road with surviving Nanyang Jigong, that she suddenly lifted the lid on this man who would have been old enough to be her grandfather. With fresh insight and patient curiosity, she continued to delve into the archives and seek out surviving volunteers in an attempt to piece together a better understanding of her father's past.

This is her account.

Chen Daya at her home in Kunming, Yunnan, during her interview with Global People in August 2025. (Photo: Liu Shuyang / Global People)

“Comrade-in-arms”

The year 2000 was when it all changed. Before then, I only knew that my father was an old overseas Chinese returnee with some connections abroad. It was only that year that I learned he was a volunteer of the Nanqiao Jigong. Some people might be wondering, "How could a daughter know so little about her own dad?"

It turns out that his situation was a little special. He was born in 1900. By the time he was recruited in 1939, he was 39 years old. At that time, applicants were required to be between 20 and 40 years old. To ensure his application was successful, my father tweaked his age by 6 years, so he was one of the oldest recruits.

My mother was 30 years younger than my father. I imagine that when she met him, he must have still been a dashing middle-aged man. But by 1962, when I was born, he was 62 years old, and to me, he felt like a grandfather.

He didn't even own a single decent outfit; he always dressed in a coarse fatigues. My father didn't fit my idea or image of what a "father" should be. I couldn't help but compare him to my classmates' fathers, who were all young, strong, and in their prime. Why did it have to be my father who was so old and always seemed to wear the same drab, dusty clothes?

Life was difficult back then; everyone received a meager rice ration, and we mostly relied on coarse grains to fill ourselves up. At mealtimes, most of our rice was "assigned" to my father. On the rare occasions when we had meat, our mother would swat away my siblings' and my chopsticks so my father could have more. As we hungrily coveted the forbidden meat, so close yet out of reach, we were always left wondering why.

My mother would say, "You're still young, you'll have plenty of chances. Your father is old, let him have his fill." The overalls he wore daily, made of sturdy fabric, enveloped a pure cotton undershirt underneath, issued by his workplace. On the front, in large print, was the character 奖 ("Award"), presented to him for 100,000 kilometers of safe driving. This undershirt was often swapped out for another, which was a reward for being honored as a "Model Worker."

Later, my mother told me that my father had instructed her that when he passed, he should be dressed in those fatigues. Perhaps out of embarrassment, my mother secretly made him a khaki-grey Zhongshan suit for that occasion—the only new suit my father ever had in my memory. But he got his wish, and died in the very clothes I had seen him wear day after day since I could remember.

When it came to him, I kept my distance, so I knew absolutely nothing about his life.

That all changed in October 2000. I was at work when I received a call out of the blue. The person on the other end told me about an event sponsored by Mr. Tan Keong Choon, the nephew of famed Chinese philanthropist Tan Kah Kee, to retrace the path of the Burma Road, and asked if I would be willing to go. Although I didn't know what it would involve, I agreed, knowing how difficult it would have been to go there otherwise and how rare an opportunity it was.

More than a dozen of us set out from Kunming, three of whom were Nanqiao Jigong volunteers who were still alive at the time and were close friends of my father during his lifetime—Luo Kaihu, who, like my father, was Hainanese, and with whose family we maintained close contact; Weng Jiagui, whose home in Hainan was only a few kilometers from my father's home; and Wang Yaliu, who always had the greatest respect for my father.

On our way to Dali, we listened to their stories. After our arrival, we took part in a symposium where everyone took turns sharing stories about themselves or their parents' generation.

When others spoke of their fathers, they spoke their moving words eloquently, with tears in their eyes. Then it was my turn. Except I had nothing to say. Thankfully, Uncle Weng came to the rescue: "Allow me. Her father, Chen Zhaozao, used to live in Singapore, where he and his brother owned a trading company that did very well. Her father was Hainanese and loved singing Qiong (Hainan) opera the most. His vehicle repair skills were second to none. He was also a good person, and because he was a bit older, we all called him 'Da Bo' (Elder Uncle)."

A group photo taken at a gathering of Nanqiao Jigong in Kunming in 1982. Chen Zhaozao is fourth from the left in the front row. (Photo provided by Chen Daya)

This was the first time I had heard someone else tell my father's story. I secretly thought to myself, "So, my father was a pretty remarkable person after all."

We continued on our way. When we arrived at Xiaguan, Uncle Weng pointed to an empty plot of land and said to me, "Daya, look! This was the site of the Eighth Automobile Repair Shop of the Southwest Transportation Office. This is where your father worked."

Then we arrived at Huitong Bridge. Looking at the surging Nu (Salween) River below, Luo Kaihu recalled those thrilling times driving across the bridge. Then, facing the river, he yelled, "Comrades-in-arms! Compatriots! Today, we've come to see you!"

I was profoundly moved. When I was a child, I watched the revolutionary war movie Eternity in Flames (《烈火中永生》). I thought that only revolutionary martyrs like the lead protagonist, Sister Jiang, were worthy of the title "comrades-in-arms." How was it, then, that my inconspicuous, silent, elderly father was also a "comrade-in-arms"? There, by Huitong Bridge, my heart began swimming in a sea of emotions. I made a decision: I needed to learn more about these "comrades-in-arms."

So young, so vibrant

After I returned to Kunming, I spent almost all my free time deep among the shelves of the Yunnan Provincial Archives, reading files, flipping through books, and collecting and organizing information about my father and the Nanqiao Jigong. However, finding and making sense of the information turned out to be a Sisyphean undertaking. It had been many decades since the events had occurred, many places were involved, and the people with first-hand knowledge of them began dwindling. Even if I came across a survivor, it was sometimes difficult to get more than a few words from them.

I also visited my father's old workplace, where I uncovered his notes. Bit by bit, I slowly pieced together his early life.

Chen Zhaozao was born on September 5, 1900, in Fenglou Village, Lehui County (now Qionghai City), Hainan. As a child, he studied for one year in a local traditional private school (Translator's note: this kind of private school is not synonymous with modern private schools. It was typically a small, single-classroom school set up by a local scholar to provide basic, Confucian-centered education to children in the village in return for a small fee.) When he was 8 years old, his mother fell sick and passed away, so he stopped his studies and went home to help his father farm, herd cattle, and make ends meet. Later, his elder brother Chen Zhaoqin went to Singapore.

At the age of 16, faced with the challenge of making his own way, he joined his brother in Singapore. He first learned tailoring at a trading firm before going on to become a handyman for a British family. Two years later, he entered a factory run by the British as an apprentice, learning electrical maintenance, driving, and other skills. By the age of 20, he was already skilled in trades such as machine maintenance and truck driving. Later, he worked on an ocean liner as a mechanic, secretly learning how to make pastries, brew coffee, and speak basic conversational English in his free time.

He and his elder brother also partnered with two fellow villagers from their home in Hainan to open the then relatively famous “Tianhetang Pharmacy” in Singapore. It ended up doing very well, and their families went on to live a prosperous life.

Those years left an indelible imprint on my father. I remember when I was little, my father would take me to the cafe to have coffee. My mother also mentioned that my father was very particular; before going out, he would always take a small brush and meticulously brush down his jacket. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, mass literacy classes were established for older learners. My father encouraged my mother to attend, even giving her a Parker fountain pen.

It was the War of the Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression that brought my father back to China. In July 1937, the Lugou (Marco Polo) Bridge Incident, a battle between Chinese and Japanese forces near Beijing, occurred. Learning that China was recruiting mechanics to aid the war effort, my father signed up and returned to China from Singapore.

Many years later, I visited Singapore, where I met the president of the Hainan Tan (Chen) Clan Association. Upon learning who I was, he took out a booklet commemorating the 50th anniversary of the association's founding, and to my surprise, I saw that my father and his elder brother were listed among the founders. The document stated that the association's purpose was to help clan members, raise funds, and support the Chinese war effort. Seeing this, I realized that my father's decision to enlist and return to China was no mere coincidence.

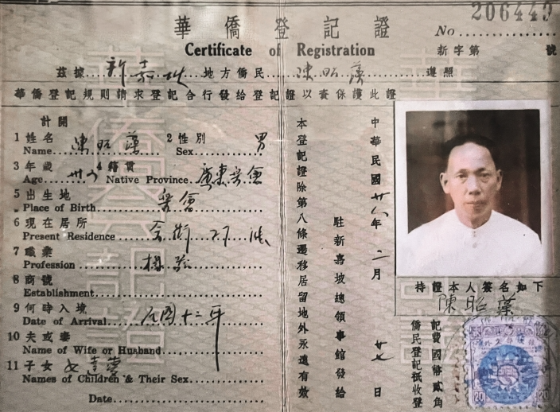

After much research, I finally happened upon the image of the "father figure" that had, up to that day, only existed in my imagination. That day, as I was flipping through documents, he suddenly "jumped out"—an overseas Chinese registration certificate with the serial number 206449 issued by the Chinese Consulate General in Singapore on the eve of the return of the Nanqiao Jigong to China in 1939. Affixed was a photo of my father in his younger years: a high forehead, deep-set eyes, a clean white round-neck shirt, and meticulously combed hair neatly swept back.

Chen Zhaozao's overseas Chinese registration certificate has been lovingly framed by his daughter, Chen Daya, and takes pride of place on a wall in her home. (Photo: Liu Shuyang / Global People)

This discovery overwhelmed me. My hands trembled as they held the certificate, and tears streamed down my face. The old man who had been the only father I knew was once so young and vibrant. However, in this encounter, we were already separated by time and space.

On March 13, 1939, my father boarded the ocean liner Fengxiang at Taikoo Wharf in Singapore and set off for home. He was part of the second cohort of Nanqiao Jigong, totaling 207 people.

On April 1, after a week of intensive training in Kunming, 24 men of Hainanese origin, including my father, along with some other overseas Chinese recruits, were assigned to an automobile repair and assembly plant temporarily set up by the Chinese government in Yangon, Myanmar to assemble a large number of US Dodge and Autocar trucks in preparation for urgently transporting military supplies.

The US engineers originally planned for groups of six to assemble one new truck per week. However, my father and his colleagues, braving the elements, worked continuously for over 10 hours every day, upping their numbers from two trucks per day to six. Their efficiency awed their US counterparts.

Later, a fellow engineer told me that in addition to my father and his workmates' experience and skills, they had brought dozens of boxes of tools with them from overseas, including a non-destructive magnetic particle flaw detector, which was highly advanced for its time. Trucks on the Burma Road ran constantly back and forth amid shelling and gunfire. This instrument could detect metal fatigue cracks on automobile parts that would be invisible to the naked eye.

From Yangon, Myanmar, to Xiaguan, Yunnan, and then back to Lashio, Myanmar, my father drove, racing day and night along the Burma Road. It wasn't until May 1942, when Japan occupied Myanmar and bombed the Huitong Bridge, that the Burma Road was cut off, and the Nanqiao Jigong were disbanded. My father left and took a job at the US Army Repair Shop at Kunming East Station. Later, he also served as a pastry chef at US Air Force guest houses in Wujiaba, Kunming, and Yunnanyi near Dali.

A worthy trade-off

The search for my father's story enabled me to gain a deeper understanding of the Nanqiao Jigong and their historical context.

Their contribution to China's war effort and national reconstruction was a labor of love, unconstrained by personal losses and gains. As veteran mechanic Wang Yaliu told me: "Be it during the war period or later during national reconstruction, the Nanqiao Jigong gave their all for their country."

During the War of the Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, their monthly salary was just a little more than 30 yuan. My research revealed that in their original places of residence abroad, their monthly income, converted to the currency of the Kuomintang-controlled areas at the time, came out to about 700 yuan. In addition to their salary, they were sometimes given bonuses for meritorious conduct, including "10 yuan for the emergency transport of supplies in Baoshan," "40 cents for emergency transport near Kunming," and so on. In reality, these rewards were a drop in the bucket for them, but that never stopped them from sacrificing their time, rich salaries abroad, and—in many cases—their lives.

One Nanqiao Jigong named Huang Changwen was once awarded 10 yuan for his meritorious service in providing emergency transport. During the trip along the Burma Road in October 2000, we reached a mountain pass. Here, Wang Yaliu sighed, saying that back then, this was the most treacherous place above the Nu River. Poignantly, he added that it was here that Huang Changwen's vehicle overturned. His remains were never recovered.

Another story of sacrifice comes from a man from Hainan, who bore the same surname as I. His convoy was attacked by enemy aircraft, spelling his end. Later, when his remains were recovered, he was found with his head blown off, but his body remained upright in the driver's seat, his hands tightly gripping the steering wheel.

These are the stories of victims who were able to be identified. Many more who made the ultimate sacrifice remain nameless to this day. It is in memory of their sacrifices that I have tried to tell the story of the Nanqiao Jigong through various forms over the years, including establishing the Burma Road Experience Hall, organizing trips to retrace the road, and creating the dramatic song cycle Ode to Nanyang.

The dramatic song cycle Ode to Nanyang was performed at the Kunming Memorial Hall to Victory Against the Japanese on September 3, 2018.

In 2015, we performed the Ode to Nanyang song cycle in Malaysia. The next day, a Chinese-language media outlet published the headline “Let the Heroes Find Their Way Home.” I kept looking at it, weeping as I did.

After all these years, I finally knew my father. As for his legacy? Giving me the opportunity to immerse myself in this period of history.

Today, the term "Nanqiao Jigong" and the people and stories it embodies have been my constant support. Throughout one's life, one is constantly faced with choices. Looking back at them, their choice was clear: to serve the greater good, for our people and country.

Discovering Mysteries Season 5, Episode 12: Love Ballad of the Rainforest Frog

05:26, 22-August-2025A Hainan media tour for journalists across 9 Asian countries

05:26, 22-August-2025Expert Talks: Hainan: New Foreign Investment Hotspot

05:26, 22-August-2025Chen Zhaozao: Life and Death on the Burma Road

05:26, 22-August-2025ASEAN Media Explore Wanning’s Cultural Treasures

05:29, 21-August-2025ASEAN Media Wowed by Sanya's "Artificial Ocean"

05:29, 21-August-2025By continuing to browser our site and use the services you agree to our use of cookies, Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.